- UGREEN

- Posts

- India becomes the largest rice exporter in the world. How the privatization of Sabesp impacts São Paulo

India becomes the largest rice exporter in the world. How the privatization of Sabesp impacts São Paulo

Your UGREEN News is live!

News

Record rice exports in India accelerate the overexploitation of aquifers in the country’s north

Credits: Reuters

India consolidated its position in the 2024–25 fiscal cycle as the anchor of the global rice market. Exports exceeded 20 million metric tons (MMT) and generated USD 12.95 billion, despite tariff shocks and geopolitical instability along Red Sea shipping routes. Behind these figures, the report identifies a structural ecological crisis: large-scale rice exports effectively amount to exporting groundwater, placing increasing pressure on aquifers in the states of Punjab and Haryana.

The document describes the current model as a “water bubble,” sustained by environmental arbitrage: the cost of water is not reflected in the final price of the grain. According to the analysis, commercial leadership is maintained through a cost structure that operates disconnected from the trend of hydrological depletion in northern India.

Recovery and record volumes

After a period of volatility and restrictions in 2023, driven by concerns over domestic inflation and the El Niño phenomenon, India recalibrated its trade policy in the 2024–25 cycle. The lifting of restrictions on non-basmati rice and the removal of Minimum Export Prices (MEP) fueled the recovery of shipments.

The report indicates that India accounted for more than 40% of global trade and exported to over 170 countries, reaffirming its central role in the market.

Accordingly, the snapshot of this cycle can be summarized as follows:

Total: 20.1 MMT | USD 12.95 billion | +6.2%

Basmati: 6.06 MMT | USD 5.87 billion | +14% in value

Non-basmati: 14.04 MMT | USD 7.08 billion | +3.5% in volume

Asymmetric dependence

The analysis describes a concentrated global dependence, in which the food security of entire regions is tied to the political and climatic stability of a few Indian states.

In the Middle East, India holds 58% of the regional market. Countries such as Saudi Arabia and Iran rely heavily on Indian basmati, described as a relevant component of diplomatic and commercial relations.

With regard to West Africa, the report points to vulnerability. India controls 41% of the regional market. The case of Benin (a West African country) is used to explain the logistics mechanism. In 2024, the country imported USD 853 million in rice, with the port of Cotonou operating as a hub for informal re-exports to Nigeria, which maintains strict protectionist policies.

The decline in non-basmati and ecological “dumping”

India maintained competitiveness through strong basmati prices and aggressive adjustments in non-basmati. The report records:

Basmati (variety 1121): USD 1,050–1,120/ton (FOB)

Non-basmati (5% broken): from USD 560 (Apr/2024) to USD 505 (Jun/2025), after removal of the MEP

This drop was described as decisive in regaining market share in Africa vis-à-vis Thailand and Vietnam. At the same time, the text argues that the low price does not reflect the true cost of water resources, characterizing “ecological dumping”: groundwater is consumed without being priced into the exported grain.

Indian states under hydrological stress

The core of the document is hydrogeological. The states of Punjab and Haryana, celebrated as India’s “breadbasket” since the Green Revolution (1960), operate under structural water deficit. Producing 1 kg of rice in these regions consumes between 3,000 and 5,000 liters of water.

The compiled indicators point to overexploitation:

Punjab: average extraction rate of 156% of annual recharge;

Overexploited blocks: Punjab 72.55% (111 of 153), Haryana 63.64%;

Water table decline: from 30 feet (~9 m) to 80–200 feet (24–60 m) by 2025;

Projection (upper layer): risk of depletion in Punjab by 2029.

The report also highlights the human dimension: accounts of farmers spending between INR 30,000 and 40,000 in a single season to deepen wells and install longer piping. In Haryana, the need for higher-capacity submersible pumps emerges as a factor squeezing margins and increasing indebtedness.

“Virtual water” leaves with the rice

The concept of “virtual water” organizes the environmental cost of trade. The report estimates that exporting 20.1 MMT of rice implies virtually exporting around 40 to 50 billion cubic meters of water.

It also notes that in 2023–24, virtual water exports via rice (40.87 BCM) represented nearly 17% of India’s annual groundwater extraction and almost 20% of total agricultural use. The sustained reading is that commercial leadership rests on finite reserves, with accelerated loss of natural capital.

MSP, subsidized energy, and locked-in change

The persistence of rice cultivation in water-scarce regions is not treated as an “ecological mistake,” but as the result of incentives. The report describes the MSP (Minimum Support Price) and guaranteed procurement as a structure that turns rice and wheat into lower-risk crops. The guaranteed price of rice is estimated to have increased by around 70% over the past decade.

Energy subsidies close the loop: free or nearly free electricity for irrigation effectively removes any cost signal for water use, despite the social cost of aquifer depletion.

When diversification is discussed, the text records the collapse of alternatives in the field. In Punjab, cotton acreage reportedly fell from nearly 600,000 hectares to around 100,000 hectares in 2024–25, associated with the pink bollworm pest and the declining effectiveness of BT cotton, alongside delays in approving new technologies. On the political front, resistance is described as structural: recurring protests and low uptake of temporary incentives to shift from rice to millets (such as INR 17,500/ha in Haryana), as they fail to address long-term market risk.

Exporting volatility and global impact

The report describes rapid cycles of scarcity and surplus that destabilize dependent economies. In West Africa, the “whiplash effect” is clear: restrictions in 2023 pushed prices up and triggered panic; reopening in 2024–25 brought cheap rice, putting pressure on local producers.

Senegal is presented as a case of reversal at the end of 2025: six months of stocks (double the normal level), around 195,000 tons of local paddy rice stranded, and a temporary suspension of imports in November 2025. The episode included vessel diversions and a drop in the price of Indian broken rice to USD 298/MT, affecting exporters.

Solutions and interventions: technology, scale, and limits

The main technical alternative highlighted is Direct Seeded Rice (DSR). The report notes potential water savings of 20% to 40% and reduced labor requirements, supported by a subsidy of INR 1,500/acre in Punjab and satellite (SAR) verification. Barriers are also clear: more complex weed management and the risk of failure if early rains are irregular.

In the corporate sector, initiatives involving PepsiCo and Olam Agri, in partnership with the Alliance of Biodiversity International, are cited, as well as PepsiCo’s work with more than 27,000 farmers in India. The report, however, emphasizes limitations of scale relative to the total number of producers and dependence on incentives outside the structural subsidy framework.

Conclusion

The report argues that India’s leadership in global rice trade in 2024–2025 rests on conditions that increase medium-term risk. Record export volumes coexist with aquifer overexploitation in Punjab and Haryana, deepening water tables, and rising extraction costs, with direct impacts on farm income and the viability of small producers.

Externally, importer dependence—especially in West Africa—amplifies the transmission of instability: domestic Indian decisions generate cycles of scarcity and surplus, affecting prices and local policies, as illustrated by Senegal’s temporary import suspension in November 2025 following stock accumulation and unsold domestic production.

UGREEN

The UGREEN Sustainable Shift is what your career needs for 2026!

Start the year leading the sustainable transformation. Spots are already filling up, act fast!

You know it was a success. And if you’re not part of it yet, this is your perfect opportunity.

All spots were filled quickly, and we realized many professionals are still looking to join this movement.

That’s why we’ve opened a new opportunity to secure:

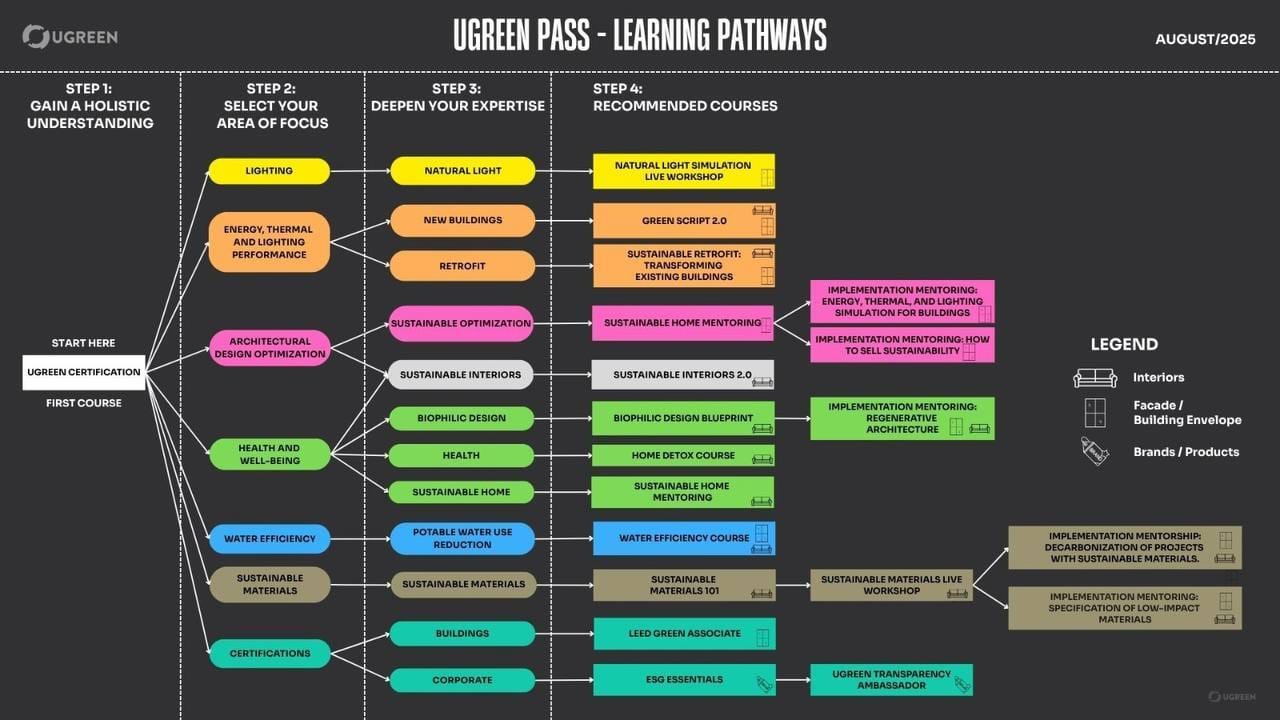

Lifetime access to ALL UGREEN courses;

All courses for the price of one;

Complete learning paths (so you know exactly what to study and in what order).

The UGREEN Pass was created for those who want to turn sustainability into a real business advantage.

With it, you’ll learn how to:

Sell projects using data (not opinions);

Charge more by delivering efficiency;

Work with retrofitting and sustainability certifications;

Position yourself as a recognized specialist.

See below how many courses you’ll unlock:

👉 There’s still time to transform your career for 2026!

Video

Water as a right … or as an asset?

The privatization of Sabesp, completed in July 2024, changed the control of sanitation services in São Paulo. Management shifted from state ownership to private control, altering how priorities, investments, and service operations are defined.

The central issue is not only “who manages,” but how decisions are made: long-term infrastructure projects now compete with short-term targets, the governance structure changes, and regulation takes on a more significant role.

In the 2024–2025 debate, three themes consistently emerge:

service supply and continuity, especially during periods of system stress;

internal operational and workforce changes, including restructuring;

Want to understand what Sabesp’s privatization changes in practice?

Watch the full video on the topic and explore in detail the impacts of the privatization of the São Paulo State Basic Sanitation Company.

Disclaimer: The video is in Brazilian Portuguese, but simultaneous translation and subtitles are available in multiple languages.

Reply